News & History

The Glenn A. Harper Endowment Fund

Ohio National Road Association founding member Glenn Harper. Started this endowment in 2009 to continue his passion for the National Road and its preservation. This endowment will be the source of matching funds or total funding for specifically selected preservation projects along the Ohio Historic National Road. For more information and application please use the button below to email the Ohio National Road Association.

Ohio Historic National Road Receives National Byway Leveraging Resources Award

MILLERSBURG, OH (April 15, 2025) – The National Scenic Byway Association is proud to recognize the Ohio Historic National Road with the 2025 Byway Leveraging Resources Award, celebrating their collaborative educational program that brings history to life for local students through an immersive Blaine Bridge Day annual event.

Led by the Ohio National Road Association and a team of community partners, Blaine Bridge Day engages fifth-grade students from Bridgeport Middle School in a hands-on exploration of the historic 1828 Blaine S. Bridge, Ohio’s Bicentennial Bridge and a designated National Register landmark. The event combines local history with interactive learning, featuring wagon rides, period games, art projects, and even antique car displays.

“We want students to experience history, not just read about it,” said Cathryn Stanley, who helped organize the program. “Blaine Bridge Day helps kids connect with their community’s past in a meaningful, memorable way.”

The program is the result of strong partnerships between the Ohio National Road Association, Pease Township Park District, Bridgeport Exempted Village School District, and the Belmont County Tourism Office. With support from local educators, volunteers, and government officials, including the Belmont County Engineers Office and Ohio Department of Transportation District 11, students learn firsthand about the construction, restoration, and historical impact of the bridge and the road it serves. Authorized by Congress in 1806, the National Road was the first federally funded interstate highway in the U.S., and its path through Ohio shaped the growth of towns, trade routes, and westward expansion.

Blaine Bridge Day brings this history to life while reinforcing the byway’s role as a valuable educational and cultural resource.

“By connecting students with the past through real-world experiences, this program shows how byways can inspire the next generation,” said Sharon Strouse, Executive Director of the National Scenic Byway Association. “It’s a perfect example of how partnerships and creative thinking can make a lasting impact using existing local resources.”

Learn more about the Ohio Historic National Road Byway at www.ohionaonalroad.org and www.travelbyways.com.

###

The National Scenic Byway Association, a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, serving as The National Voice of Scenic Byways and Roads, dedicated to strengthening Byways through education, training, and shared expertise. It is the vision of the National Scenic Byway Association that our nation’s designated Byways

will be recognized and valued worldwide for their distinctive experiences, stories, and treasured places.

For more information visit www.nsbfoundaon.com; www.travelbyways.com; or email: sharon.strouse@nsbassociaon.com

Intel "Super Load" uses Historic National Road in Licking County!

Can you imagine 916,000 pounds, 23' tall, 20' wide and 280' long, Intel cold box, traveling down the Historic National Road in Licking County? It happened!

Watch the moving road block here!

Ohio Department of Transportation 7/31/24 news release.

National Road History Videos

Ohio ByWay Videos

Please click here to see all the Ohio ByWays latest videos.

New video - Johnny Appleseed Historic ByWay

America 250 Ohio Commision

Please keep in mind that Transportation is the theme in April 2026 for the America 250 Celebration

Licking County first to complete historic mile marker set!

Licking County is the only county in Ohio - and maybe even the country that has a complete set of original and repalcement National Road mile markers. What makes this fact more impressive is that Licking County's 10% portion of the Ohio National Road (US-40) is the largest, covering 30-miles and now with a complete set of 30 markers.

Jim Young and Sandy Gartner board members of the Ohio National Road Association made it their mission to replace the last three Licking County missing markers 215, 221 and 224. With the help of grants from the Cecil Mauger Charitable Trust, Licking County Commissioners, Licking County Historical Society and with the installation by the Ohio Department of Transportation, they accomplished their goal.

Howard Long, Executive Director of the Licking County Historical Society: "This achievement not only honors our rich history but also serves as a testament to the community’s dedication to preserving our cultural heritage. Each mile marker stands as a symbol of our past, guiding us through the journey of our nation's development."

The Licking County Historical Society is dedicated to preserving, protecting, and promoting the history and heritage of Licking County. Through various initiatives and projects, the society strives to educate and engage the community in understanding and appreciating the county’s historical significance.

Thomas P. Barrett, ODOT Historic Bridge Program Manager and State Byways Coordinator stated, "We are pleased to announce that three of our mile markers are back in place in Licking County on the nation’s first highway. Thanks to the Ohio National Road Association and ODOT’s District 5 Highway Technicians, the historic stone mile markers are securely in place for future generations of travelers to enjoy. The Licking County markers are part of a larger project that ODOT and ONRA are partnering on to get all the original mile markers back in place along the historic route, dating to 1830."

July 4th,1825 construction started on the 228-mile portion of the Ohio national road at Bridgeport, Ohio crossing 10 counties to the western Ohio border. By 1832 the road had crossed through Licking County on its way to Columbus. Under the Thomas Jefferson administration congress had authorized the construction of the 700-mile National Road from Baltimore, Maryland to East St. Louis, Illinois. That authorization included the requirement that mile markers had to be placed every mile along the way. Due to wear and tear, road realignment over the years many of the original markers have been lost or replaced.

New location for Milestone 161.

Mile marker 161 has been saved and relocated to Guernsey County Ohio Cambridge City Park. The original milestone location site was destroyed by the advent of I 70. Thoughtful people saved markers 161 and 171 for a long time at the new World Heritage site in Licking County. OHC historian Dave Adair says, "They are some of the oldest man made things in Guernsey County and in Ohio." Send chills! Soon marker 171 will be placed at Guernsey County Fairgrounds.

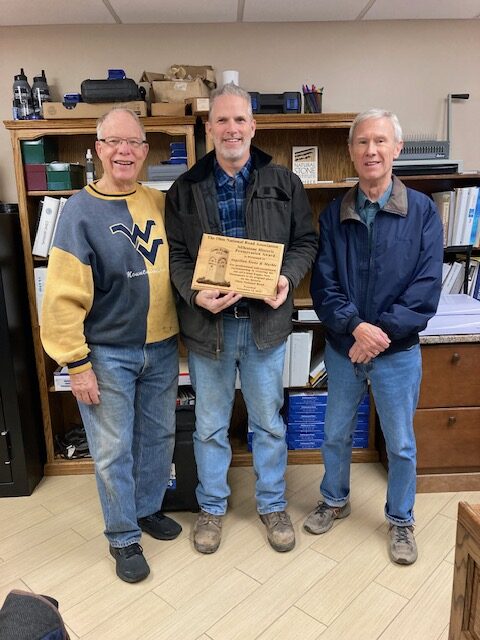

Milestone Historic Preservation Award Recipient

ST. CLAIRSVILLE OH (November 28, 2023) – The Ohio National Road Association recently presented the prestigious Milestone Historic Preservation Award to Mark White of Angelina Stone & Marble of Bridgeport for their work restoring a unique feature on the National Road in Licking County.

ST. CLAIRSVILLE OH (November 28, 2023) – The Ohio National Road Association recently presented the prestigious Milestone Historic Preservation Award to Mark White of Angelina Stone & Marble of Bridgeport for their work restoring a unique feature on the National Road in Licking County.

ONRA members John S Marshall and Jeff Aland presented the award to White , the project engineer for Angelina’s restoration of the Eagles Nest Monument in Licking County. The plaque, sponsored by ONRA Board Member Mike Peppe, reads: “For professional and exceptional workmanship in restoring the one-of-a-kind Eagles Nest Monument to its original glory on the Historic National Road.”

, the project engineer for Angelina’s restoration of the Eagles Nest Monument in Licking County. The plaque, sponsored by ONRA Board Member Mike Peppe, reads: “For professional and exceptional workmanship in restoring the one-of-a-kind Eagles Nest Monument to its original glory on the Historic National Road.”

Known as Eagles Nest, the large granite rock commemorates the experimental paving of a 29-mile section of the National Road from Zanesville to Hebron between 1914 and 1916. Arch W. Smith, of the Ohio State Highway Department called the newly paved highway “the model concrete road of the world.” Chiseled in the granite rock are renderings of a Conestoga wagon, an early automobile, and the distances to Columbus (32 miles) and Cumberland, Maryland (220 miles).

The ONRA award program recognizes individuals and organizations doing their part to help preserve, promote, and enhance the Historic National Road in Ohio.

American History - The National Road Begins

Cumberland Road one and one-half miles west of Brownsville, Pa. Library of Congress. (Public Domain)

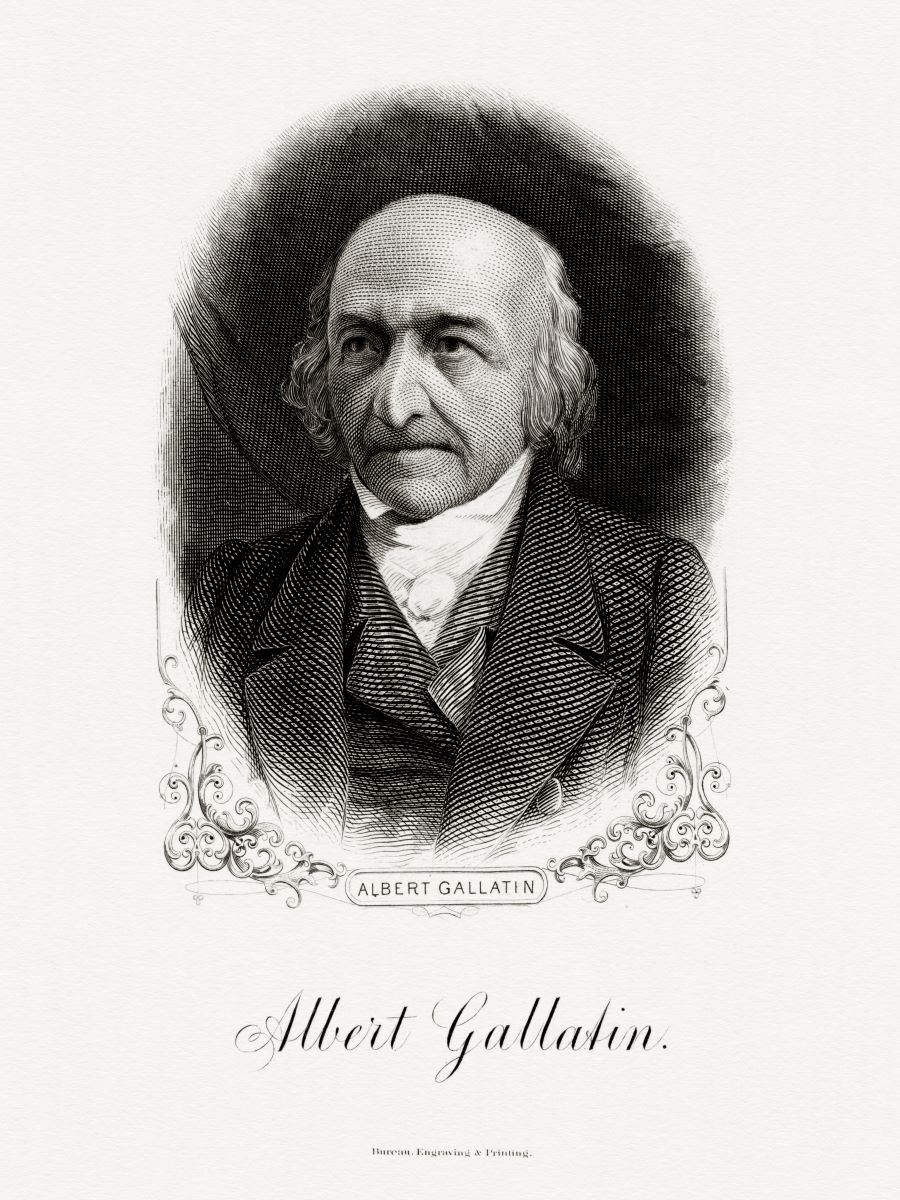

With the purchase of the Louisiana Territory, America’s size nearly doubled overnight. Greater westward expansion was now possible and necessary. As famous expeditions were conducted to survey and explore the new lands, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin believed America should immediately begin constructing roads to move people west. His vision became the country’s first national highway.

How a Treasurer Guided America Toward Its First National Highway

Because the Louisiana Purchase doubled the country’s size, U.S. Treasurer Albert Gallatin suggested a method to quickly expand west.

Bureau of Engraving and Printing portrait of Gallatin as secretary of the treasury. (Public Domain)

By Dustin Bass

“I feel not, however, any apprehension that France intends seriously to raise objections to the execution of the treaty,” Albert Gallatin wrote to President Thomas Jefferson on Aug. 31, 1803. “Unless intoxicated by the hope of laying England prostrate, or allured by some offer from Spain to give a better price for Louisiana than we have done, it is impossible that Bonaparte should not consider his bargain as so much obtained for nothing; for, however valuable to us, it must be evident to him that, pending the war, he could not occupy Louisiana, & that the war would place it very soon in other hands.”

Since March 1801, Gallatin had served as secretary of the treasury, a position he held for nearly 13 years—the longest tenure in the U.S. Department of Treasury's history. He was one of the most brilliant and successful treasurers as well.

The Swiss-born American congressman accepted the secretarial post because of his concern for “the Nation’s Debt.” When Gallatin became treasurer, the country had a debt of approximately $80 million. By the end of his tenure, he had cut the debt nearly in half.

The national debt, however, seemed to go the opposite direction when Napoleon Bonaparte offered the Louisiana Territory for sale. Gallatin saw the opportunity to purchase Louisiana—nearly doubling the country’s size for only $15 million—as an opportunity that could not be missed. It couldn’t be missed for two reasons: It would enable westward expansion, and it would therefore guarantee economic expansion.

Less than two months after Gallatin’s letter to Jefferson, which also laid out how the purchase would be financed, the Senate ratified the Louisiana Purchase Treaty.

Supporting Expeditions

Gallatin believed the Louisiana Territory would help lower the debt through the sale of land, as well as by increasing trade up the Mississippi River. Now that America owned the Port of New Orleans, it could also raise capital by charging customs duties on imports. One important step toward all of those possibilities was finding out precisely what America now owned, and that could only be achieved through exploration. It was an undertaking strongly supported by Jefferson and Gallatin.

Before the treaty’s ratification, the Corps of Discovery, led by Capt. Meriwether Lewis and 2nd Lt. William Clark, was being organized. Congress appropriated $2,500 for this expedition toward the Pacific Ocean. (It would ultimately cost approximately $40,000.) On May 14, 1804, the Corps of Discovery began its 28-month journey that would cover 8,000 miles. It became famously known as the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Gallatin had been such a strong supporter of the expedition that when the Expedition arrived at the Three Forks of the Missouri River, they named the east fork, Gallatin River.

On Sept. 23, 1806, the Lewis and Clark Expedition returned to St. Louis. One of the greatest explorations in American history was complete. Shortly before the expedition was finished, another expedition began, led by Thomas Freeman and Peter Custis, called the Freeman-Custis Expedition, also known as the Red River Expedition. It was one of the first expeditions to explore the southwestern portion of the United States, with Congress appropriating $5,000 for the effort.

The Need for a Highway

These explorations were in lands far away and lands even further from being settled. It became imperative to expand the population to areas west of the long-established states along the east coast. The same year that the Louisiana Purchase Treaty was signed, Ohio became the nation’s 17th state. Gallatin believed it needed to be easier to reach the new state. He suggested building a federal highway (a suggestion he made possibly as early as 1802).

According to Rep. Andrew Stewart, of Pennsylvania, who was also a major advocate for a federal highway, "Mr. Gallatin was the very first man who ever suggested the plan for making the Cumberland Road."

It was during this week in history, on March 29, 1806, while the Lewis and Clark Expedition was nearing its completion and the Freeman-Custis Expedition was nearing its start, that Congress passed “an Act to regulate the laying out and making a road from Cumberland, in the state of Maryland, to the state of Ohio.”

The bill appropriated $30,000 for the road’s construction, which made it the nation’s first highway fully funded by the federal government. Construction for the “Cumberland Road,” though, wasn't immediate. It would be another five years before the first contract was signed to begin the road. In between that time, in 1808, Jefferson informed Congress that “Pennsylvania, Maryland & Virginia having, by their several acts, consented that the road from Cumberland to the State of Ohio … should pass through those states … I have approved of the route therein proposed for the said road, as far as Brownsville with a single deviation since located, which carries it through Union town.”

Perhaps not so coincidentally, Uniontown was in Fayette County, the same county Gallatin had built his now famous home called Friendship Hill, located slightly southwest of Uniontown.

Construction Begins

Starting in Cumberland on near the Potomac River, the road would ultimately extend 620 miles west by the end of its construction. Additionally, the road would connect to an older road called the Old National Pike, which stretched from Baltimore, covering 118 miles.

In 1811, the first contract and the first 10 miles of what was called the Cumberland Pike was completed; it was most famously known as the National Road and was designed to be wide enough to allow wagons to pass each other safely on both sides. The road was formed to force water to drain off to the sides.

Its design was reminiscent of the famous Roman roads.

“It is covered with a very thick layer of nicely broken stones, or stone, rather, laid on with great exactness both as to depth and width, and then rolled down with an iron roller, which reduces all to one solid mass,” wrote British writer, William Cobbett, when he viewed its construction in 1817. “This is a road made forever.”

In 1818, the National Road completed the first stretch of the highway, reaching the Ohio River in Wheeling, Virginia (now West Virginia). By this time, the National Road had achieved another name: The Main Street of America. It continued to rise in popularity as more and more people traveled westward on stagecoaches and Conestoga wagons. The road, as Gallatin had envisioned, created economic opportunity. Inns and taverns began popping up along the newly constructed highway.

Extending the National Road

There was ongoing controversy within Congress about whether or not the Legislature had the Constitutional authority to pay for and establish roads. The question became even more controversial when the Panic of 1819 coincided with the need to repair the National Road east of Wheeling and with the proposal for an additional $140,000 to pay for existing contracts. Congress apparently answered the question by continuing construction.

Construction of the road continued with the passage of the Act of May 15, 1820, which authorized Congress to appropriate funds to pay for the National Road’s extension. It was planned from Wheeling through the states of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois (the latter two had become states in 1816 and 1818, respectively) and reaching “the left bank of the Mississippi river … between St. Louis and the mouth of the Illinois river.”

The following decade, the federal government agreed to cover ongoing repairs of the National Road, while states constructed toll houses. By the 1830s, the road reached its final destination: the short-lived capital of Illinois, Vandalia.

Construction ended due to lack of federal funds, but the road had proven immensely useful. The 1840s witnessed the height of the road’s success in the 19th century. By the 1850s, however, traffic substantially decreased with the rise of the railroads.

The Decline and Rise of the Road

The transcontinental railroad was a more efficient mode of transportation, specifically for longer travel. The journey, wherever one wished to travel, was faster and more comfortable.

“The national turnpike that led over the Alleghenies from the East to the West is a glory departed,” stated an 1879 article in Harper’s.

The National Road remained in operation, and a good thing it did, because its glory was soon to return. By the end of the 19th and the start of the 20th century, a new form of transportation was gaining in popularity: the automobile.

Perhaps Gallatin never envisioned an invention quite like the automobile, but his vision for what the road could provide for America proved prescient and capable of adapting to changing times and technologies.

Early in the 20th century, Congress passed several laws to create and maintain federal highways, such as the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916 and the Federal Highway Act of 1921. The latter instituted a national highway system that enabled transcontinental travel. Roads, including the National Road, began to interconnect with the national highway system.

According to the National Road Heritage Foundation, “Now, the new Historic National Road, U.S. Route 40, is the busiest it has been since its heyday of the 1840s.” By the 1920s, the road had become America’s primary method of travel and has remained so to this day.

Historical Highlights

For more in-depth history concerning sites along the Ohio Historic National Road, continue reading below.

Roadside advertising by local, regional and national companies took many forms in the early 20th century, starting with small signs promoting local inns, service stations and other businesses. Later, larger companies such as “Standard Oil” and “Old Reliable Coffee” advertised along the Road. The “Mail Pouch Tobacco Company” was perhaps the most creative of the early 20th century advertisers promoting their product on the sides of barns. Today, the ubiquitous “Mail Pouch” barn sign can still be found along the Road and throughout the Midwest. Harley Warrick, from Belmont, Ohio, painted hundred of “Mail Pouch” barn signs for nearly one-half century.

“Mail Pouch Tobacco Company” was perhaps the most creative of the early 20th century advertisers promoting their product on the sides of barns. Today, the ubiquitous “Mail Pouch” barn sign can still be found along the Road and throughout the Midwest. Harley Warrick, from Belmont, Ohio, painted hundred of “Mail Pouch” barn signs for nearly one-half century.

Burma Shave, a popular shaving cream of the day, sold in small glass jars with metal lids, began advertising in the 1930s and 1940s and eventually became one of the most prolific of the roadside advertisers. Burma Shave had a group of salesmen who would approach local landowners seeking to place a series of five, small red signs with white lettering, located about 100 feet apart, each containing one line of a four line couplet and the obligatory fifth sign advertising Burma Shave.

eventually became one of the most prolific of the roadside advertisers. Burma Shave had a group of salesmen who would approach local landowners seeking to place a series of five, small red signs with white lettering, located about 100 feet apart, each containing one line of a four line couplet and the obligatory fifth sign advertising Burma Shave.

In 1796 Ebenezer Zane won a commission from Congress to construct a new route to the west. This trace or path followed earlier animal and Native American foot-paths, winding its way from Wheeling, Virginia (now West Virginia) to Limestone, Kentucky (now Maysville). In 1803, the new Ohio legislature provided funds to widen and upgrade the road. Many towns that later prospered as a result of their location along the National Road, owe their origins to Zane’s Trace. Zane’s Trace seems to follow the long access of ridge tops as high ground was more defensible and better drained. Surviving historical accounts of the Trace portray it as little more than a blazed trail, capable of guiding a train of pack animals but a formidable challenge for a wagon. In many places the National Road followed, paralleled or crossed the earlier road. Surviving segments have been identified in Belmont, Guernsey and Muskingum Counties.

“1823. First American Macadam Road” Carl Rakeman, 1926. The approximately 70 miles of the National Road from Bridgeport to Zanesville was the first Federal road in America constructed using the macadam technique, three compacted layers of stone laid in a trough cut slightly below grade, creating a relatively smooth, durable surface capable of shedding water.

The Act of Congress authorizing the National Road required distinguishable marks or monuments to appear at regular intervals along the Road. In accordance with this stipulation, milestones were set at one-mile intervals along the north side of the Road. However, since the act included no specifications, the design and construction material of the milestones varied. In Ohio, the markers were square with curved heads. The five-foot tall markers were set directly into the ground with about three feet exposed. Each stone indicated the distance to Cumberland, Maryland, (where the Road began), at the top center, and the name of and mileage to the nearest city or village for east and westbound travelers. The earliest milestones were fabricated of a reinforced cementitious material in the 1830s. These concrete markers weathered poorly and many were replaced with sandstone markers in the 1850s. Later, concrete was used to replace some of the sandstone markers. Eighty-three existing milestones have been documented with the greatest number in the eastern counties. By the 1920s a uniform highway numbering system, with standardized road signs, identified the National Road and U.S. 40.

Local lore has it that in 1833 a young lady from a wealthy Wheeling family, who had been courting a younger man of lesser means from Fairview, stole away in the night from her parents’ home in a coach with a particularly energetic horse. She headed for the Guernsey County town to steal away with her lover. On the third bend from the top of this hill west of Morristown, a sudden bolt of lightning spooked the horse, forcing the coach to slide and ejecting the young lady from it, breaking her neck. Afterward, the horse ran aimlessly around for three days until it was finally corraled. It is said that even today on very stormy nights, the apparition of a headless young lady astride a spirited steed can be seen riding recklessly up and down the hill.

During the early nineteenth century, inns and taverns were constructed approximately every ten miles along the Road because this was the distance a wagon or stagecoach could expect to travel in a day. These early predecessors to the twentieth century cabin camp, motor court and later, the motel, offered some respite from the rigors of interstate travel. Though some ate their evening meal and retired for the night, others lingered around the fire telling stories, exchanging experiences of the Road, singing, dancing and discussing the important issues of the day. Inns were often located at the crest of hills in outlying areas and were among the most prominent buildings on the Main Street (the National Road) of many Pike towns. Drover’s inns and services were generally simpler frame structures and located on side streets parallel to the National Road or on the outskirts of town where they could accommodate pens for livestock being driven to market. An 1831 state gazetteer listed the tiny town of Etna in Licking County with 3 taverns, 6 stores and 34 dwellings. West Jefferson in Madison County was home to 5 taverns and 6 stores.

After 1838, the federal government no longer appropriated funds for National Road maintenance, though maintenance of the Road had actually been relegated to the states earlier in the decade. To pay for maintenance, Ohio and other states began collecting tolls. Even before construction was completed, the Road had in effect become an Ohio turnpike. Toll taking locations (toll-houses) were constructed about every twenty miles along the Road and tolls were determined by the type of vehicle. According to a list of tolls from 1832, the highest tolls were for cattle and two-horse carriages. Wagons with wheels in excess of six inches in width were exempt from tolls, presumably because larger wheels were actually beneficial in compacting Road gravel. Exemptions were also made for persons traveling to and from church, funerals and places of business. Clergymen and children were also exempt. In contrast to the substantial brick and stone octagonal toll-houses in Maryland and Pennsylvania, Ohio toll-houses were generally frame side-gable structures with a recessed corner porch. Despite the $1.25 milllion in tolls collected between 1831 and 1877, the Ohio National Road languished in a deplorable condition. Tolls remained in effect in some areas until 1910.

After 1838, the federal government no longer appropriated funds for National Road maintenance, though maintenance of the Road had actually been relegated to the states earlier in the decade. To pay for maintenance, Ohio and other states began collecting tolls. Even before construction was completed, the Road had in effect become an Ohio turnpike. Toll taking locations (toll-houses) were constructed about every twenty miles along the Road and tolls were determined by the type of vehicle. According to a list of tolls from 1832, the highest tolls were for cattle and two-horse carriages. Wagons with wheels in excess of six inches in width were exempt from tolls, presumably because larger wheels were actually beneficial in compacting Road gravel. Exemptions were also made for persons traveling to and from church, funerals and places of business. Clergymen and children were also exempt. In contrast to the substantial brick and stone octagonal toll-houses in Maryland and Pennsylvania, Ohio toll-houses were generally frame side-gable structures with a recessed corner porch. Despite the $1.25 milllion in tolls collected between 1831 and 1877, the Ohio National Road languished in a deplorable condition. Tolls remained in effect in some areas until 1910.

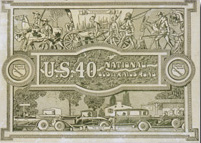

As part of their service to motorists, auto clubs, tire and oil manufacturers a nd later the federal government distributed guide books and maps for some of the nation’s roads. The highly illustrated cover of this guide highlights two of the National Road’s early twentieth century identities – as a federally numbered highway (US 40) and as the eastern-most segment of the National Old Trails Road, a consolidation of several highways to form a trans-continental route from Washington and Baltimore to California, promoted by the private National Old Trails Road Association. The cover also emphasizes the progress believed to have been made since the settlement of the nation.

nd later the federal government distributed guide books and maps for some of the nation’s roads. The highly illustrated cover of this guide highlights two of the National Road’s early twentieth century identities – as a federally numbered highway (US 40) and as the eastern-most segment of the National Old Trails Road, a consolidation of several highways to form a trans-continental route from Washington and Baltimore to California, promoted by the private National Old Trails Road Association. The cover also emphasizes the progress believed to have been made since the settlement of the nation.

Directory of Byway Information

Directory of Byway Information

Related Websites

Additional information about the Ohio National Road is available at these websites:

State of Ohio Scenic Byway Program

National Scenic Byway Foundation

MUSEUMS AND HISTORIC SITES

National Road/Zane Grey Museum

Muskingum County Historical Society

Stone Academy Historic Site and Museum

Dr. Increase Matthews House Museum and Gardens

Belmont County Heritage Museum

Clark County Historical Society

Guernsey County Historical Museum

National Museum of Cambridge Glass

Morristown Historical Preservation Association

Ohio Statehouse Museum Education Center

Bexley Historical Society & Museum

Licking County Historical Society

Preble County Historical Society & Nature Reserve

Reynoldsburg-Truro Historical Society

CONVENTION AND VISITORS BUREAUS

BELMONT COUNTY

Belmont County Tourism Council

CLARK COUNTY

FRANKLIN COUNTY

GUERNSEY COUNTY

Cambridge/Guernsey County Visitors and Convention Bureau

LICKING COUNTY

MIAMI COUNTY

Miami County Visitors and Convention Bureau

MONTGOMERY COUNTY

MUSKINGUM COUNTY

Visit Zanesville/Muskingum County

PARKS AND RECREATION

Hiking, biking, fishing, x-country skiing, and other forms of recreation:

Columbus and Franklin County Metro Parks

Muskingum Valley Park District